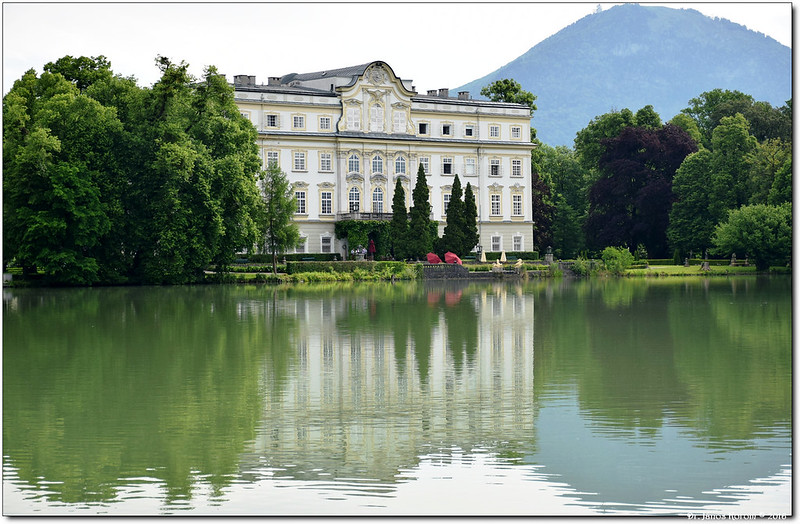

You might recognize the Schloss Leopoldskron–or, at least, the lake behind it–from the iconic canoeing scene in The Sound of Music. Given the building’s long and complicated history, however, its connection to the Hollywood classic may be the least remarkable part of its story.

The view from virtually everywhere on the Shloss’ grounds is mesmerizing. To the south is the world-famous lake, bordered by a walking path, framed by the Alps. To the north is old Salzburg, just a short jaunt away across soft, green hills and steep cobblestone streets.

I spent four days at the Schloss representing Project Kakuma at a session of the Salzburg Global Seminar. The session, called Education for Tomorrow’s World: Education and Workforce Opportunities for Refugees and Migrants, brought together educators and activists from around the world to propose strategies and solutions for meeting the needs of displaced peoples via education. The event was engrossing but exhausting, with sessions last into the late evenings. Still, every morning, I would wake before 6 am to stroll along that lake. How could I not? I had never been anywhere so beautiful.

It is the unquestionable beauty of the spot that makes its troubled history particularly jarring. The Schloss was built as a home for an 18th century Austrian bishop who financed the construction of the opulent estate by confiscating the property of Jews and Protestants he had forced to leave the region. Thus, the beautiful Schloss was actually a symbol of oppression to those who called its surroundings home.

In 1918, the Schloss was bought by actor/director Max Reinhardt. When he wasn’t directing plays on Broadway, Reinhardt was renovating his new home, which had fallen into disrepair over the past century. He turned the stately building into a place for writers, actors, and artists, even using the grounds for theatre productions.

Unfortunately, Reinhardt was forced to flee in 1938 due to the German annexation of Austria. Because Reinhardt was Jewish, the Nazis confiscated the property, handing it over to Stephanie von Hohenlohe, the wife of an Austrian diplomat who was also royalty. She was charged with turning the Schloss into a residence for visiting Nazi artists and dignitaries. However, because she was actually a double-agent, she was able to secretly send some of Reinhardt’s possessions to him in the United States.

The Schloss’ history took a different turn after the war. Reinhardt’s widow offered the Schloss to Harvard graduate student Clemens Heller who, with two other students, founded the Salzburg Global Seminar. The Seminar was envisioned as a “Marshall Plan of the Mind,” a means through which Europe could be infused with new ideas following years of totalitarianism. Since then, the Schloss Leopoldskron has hosted thinkers, politicians, and policy makers from around the world such as Kim Campbell, Kofi Anon, Saul Bellow, Hillary Clinton, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Seminar programs including Education and Work, Justice and Security, and Finance and Governance bring together people who, through policy and action, want to make the world a better place.

As I explored the Schloss, I found it almost impossible not to think about its complicated history. Who sat in this library, deep in conversation about how to make the world a better place? Did the sound of marching Nazi boots echo down this hall? Which artists found inspiration here? How did the families whose wealth built the place–families displaced, much like the people we were there to represent–fare once they were forced to leave their homes?

I suppose every building has a story.