By Risa Gluskin

Lesson design is obviously very important for every teacher, but it is especially so for teachers on the path to inquiry. While during inquiry lessons we are facilitating rather than ‘teaching’ in the traditional manner, what counts most is the scaffolding we do in the creation of our lessons.

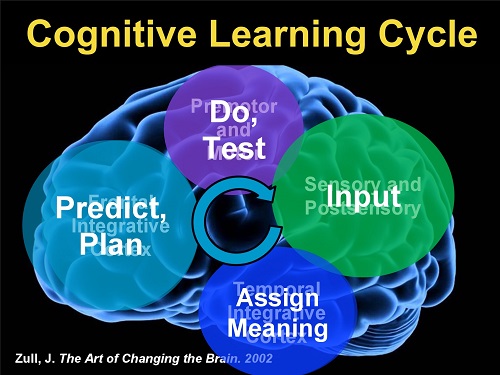

I am very lucky to have a wonderful mentor at my school who has unlocked many of the mysteries of the science of teaching for me and my colleagues. Chris Meyer is a physics teacher who has dedicated himself to inquiry teaching, constantly researching and re-designing. One of his recent interests is how to apply the cognitive learning cycle to lesson design.

Courtesy of Chris Myers

- Input

- Assign meaning to input and reflect on it, process

- Plan what to do next with ideas (abstract reasoning)

- Do/test (based on plans and understanding – must be useful knowledge)

Teachers can only participate in the input stage. The rest we can facilitate but the students have to DO.

Courtesy of Chris Meyers

If any one thing has helped me understand WHY inquiry is successful it is this: traditional teaching spends far too much time, most of our time, in fact, in the input stage. As Chris’s examination of the research suggests, we should not constantly layer on more and more information in the input stage. Despite our best intentions of sprucing up our lessons with interesting information, despite our desire to give relevant information to our students, what really matters is designing lessons so that students have time to work with the information. Students need to reflect on meaning and we need to give them time to do this.

Time and Resources

Generally, we do not lack resources and we enjoy piling them on. Generally, we lack time. How do we reconcile these two things? My current approach is to look at the curriculum as a series of topics rather than as a narrative. Having an overall course question helps with this, despite the tendency to link questions to a narrative. I tell the students that we’ll just jump in here and there and try to address certain key topics (and thus we have less and less need for a textbook). This certainly worked for me in the many years that I taught HSB4U (Challenge and Change in Society). I found the amount of curriculum expectations in social science courses to be reasonable. Not so in history.

After applying the non-narrative approach in CHY4U (grade 12 World History from 1450) for the second year, I am finding this course highly adaptable to this method. I have much larger concerns about succeeding in CHW3M (grade 11 World History to 1450). In ancient history, I have already let go of so much content that I used to teach; no longer do I linger on geography. However, I still have an intense fear of letting students jump into a civilization (a fraught term, if ever there were one) without background context. I have eliminated so much context over the years, but I still do too much direct instruction on it. It’s like an addiction. Surely my newfound awareness of the cognitive learning cycle will break me of this habit. More on that next semester when I blog about my CHW3M class.

When I get tempted to instruct (or present) rather than facilitate, I should remind myself that my most successful recent lessons have been inquiry-style with little context: things I have structured but not directly taught. For instance, in CHY4U at the beginning of the last unit, my students do an assignment on decolonization. I give them four days in the library to research a case study (Algeria, Kenya, or Ghana), plus I give them concise information on India’s experience. On the day of the assessment (of learning), students are put into mixed groups to discuss the lessons of decolonization from both the perspectives of the colonized and the colonizers. As the groups discuss (according to a list of prompts prepared by me), I am listening and recording the results on a checklist. They also have to record their lessons on whiteboards in case I miss important points (which I do). Finally, students who didn’t participate enough have the opportunity to write short reflections in their Historical Thinking Concept journals.

The discussions were very wise this time around. Not everyone participated to their fullest, but everyone wrote lessons on the whiteboards. What makes this successful is that I structure the inquiry very carefully for the students. Beginning with a note-taking organizer with a lot of guiding questions on it, I move on to the prompting questions for discussion. All of this upfront scaffolding by me allows the students to reflect on the input (research) they have gathered themselves, and to reason by coming up with the lessons. That’s three stages of the cognitive learning cycle.

The Fourth Stage: Testing

What about the fourth stage, testing? This is a whole new world for me as a history teacher, I find. Probably if I had kept on as a social science teacher I would have turned this into problem solving. I don’t find that applicable as a history teacher. So, what I have started (just very recently, very tentatively) doing for the fourth stage of the cognitive learning cycle is having students go back and re-examine their earlier interpretations/conclusions. Yes, I know, this takes more TIME. Here’s one successful example I had relatively recently with my grade 12s. In an introductory lesson on late 19th century imperialism, students had to rank the top three technologies they thought enabled imperialism (from a timeline of technologies compiled by me). After considering different advantages and disadvantages of imperialism (from both the colonizer and the colonized perspectives) and a series of maps related to imperialism, students then came back to their original ranking of the three technologies. Admittedly, it was rushed, but it was my attempt to have students test their own thinking, almost as if to bring the lesson full circle.

As I move forward in the development of my lesson design according to the cognitive learning cycle, I will try to build in more opportunities for students to reflect, plan and test. It means a lot more work in the design phase, that is for sure. However, I enjoy interacting with my students as they are learning. There’s not much interaction when I’m standing up there speaking.

Sources to Consider:

http://www.meyercreations.com/physics/presentations.html Chris Meyer’s website

http://www.thirteen.org/edonline/concept2class/constructivism/index_sub1.html Constructivism

http://ebtn.org.uk/evidence/neuroscience/ Evidence Based Teachers Network

Risa Gluskin teaches history and student success at York Mills CI in Toronto.