By Jim Pedrech

How rebuilding a city founded in the 8th century BCE is helping my students meet competencies of the 21st century

In late October, my CHW 3M students and I decided to embark on a new project: we would create a large-scale map of Rome using a cloth, a 3D printer, and whatever other resources we could muster. Ideally, this map would act as a portable museum that would help other students learn about Ancient Rome.

Students will solve meaningful, real-life, complex problems by taking concrete steps to address issues and design and manage projects.

We began by having a class discussion about the project. What, exactly, would it look like? How would we build it? How would we ensure consistency between 25 contributors? The answers were important but malleable; having had some experience with other class projects, I felt confident that our answers would change over time. We knew that we wanted to print at least one building per student: the student would conduct research about their building and produce a short sound file that would be uploaded to the cloud. Next, we would create a QR code (basically, a picture that, when scanned by a phone, takes the user to a specific link on the internet) for each sound file; each QR code would be pasted to the bottom of the appropriate 3D model, meaning that anyone with a phone could pick up the model, scan the QR code, and instantly listen to the appropriate sound file. Thus, our museum would be an interactive–and, hopefully, engaging–experience.

Students will engage in an inquiry process to solve problems as well as acquire, process, interpret, synthesize, and critically analyse information to make informed decisions (i.e., critical and digital literacy).

My two biggest concerns were pedagogical. First, how could I ensure that students were not simply regurgitating facts? As always, the Historical Thinking Concepts saved the day. By focusing on Significance, we were able to generate a simple inquiry question that not only met pedagogical requirements but also unified the students’ work: what does this building tell us about life in Ancient Rome? Simple. Clear. Purposeful.

Thankfully, my second concern was quickly alleviated. I was convinced that the biggest stumbling block would be the building selection process. What if we can’t find enough models of relevant buildings to ensure that each student is contributing? We started by creating a master list of 3D models featuring ancient Roman buildings. By searching Sketchfab, Thingiverse, Microsoft’s Remix 3D, and Google’s 3D Warehouse, we were able to find pre-existing models that we could easily print; of course, this meant that our map would have to include appropriate citations to credit the appropriate 3D modellers. However, we couldn’t rely exclusively on pre-built models because some were intended for 3D viewing, not 3D printing; in some cases, our program wouldn’t recognize the model at all. Thus, those students interested in tech got a crash course in 3D Builder, a free app from Microsoft, and began designing their own versions of important buildings. Roughly half of our buildings were made by students or by me.

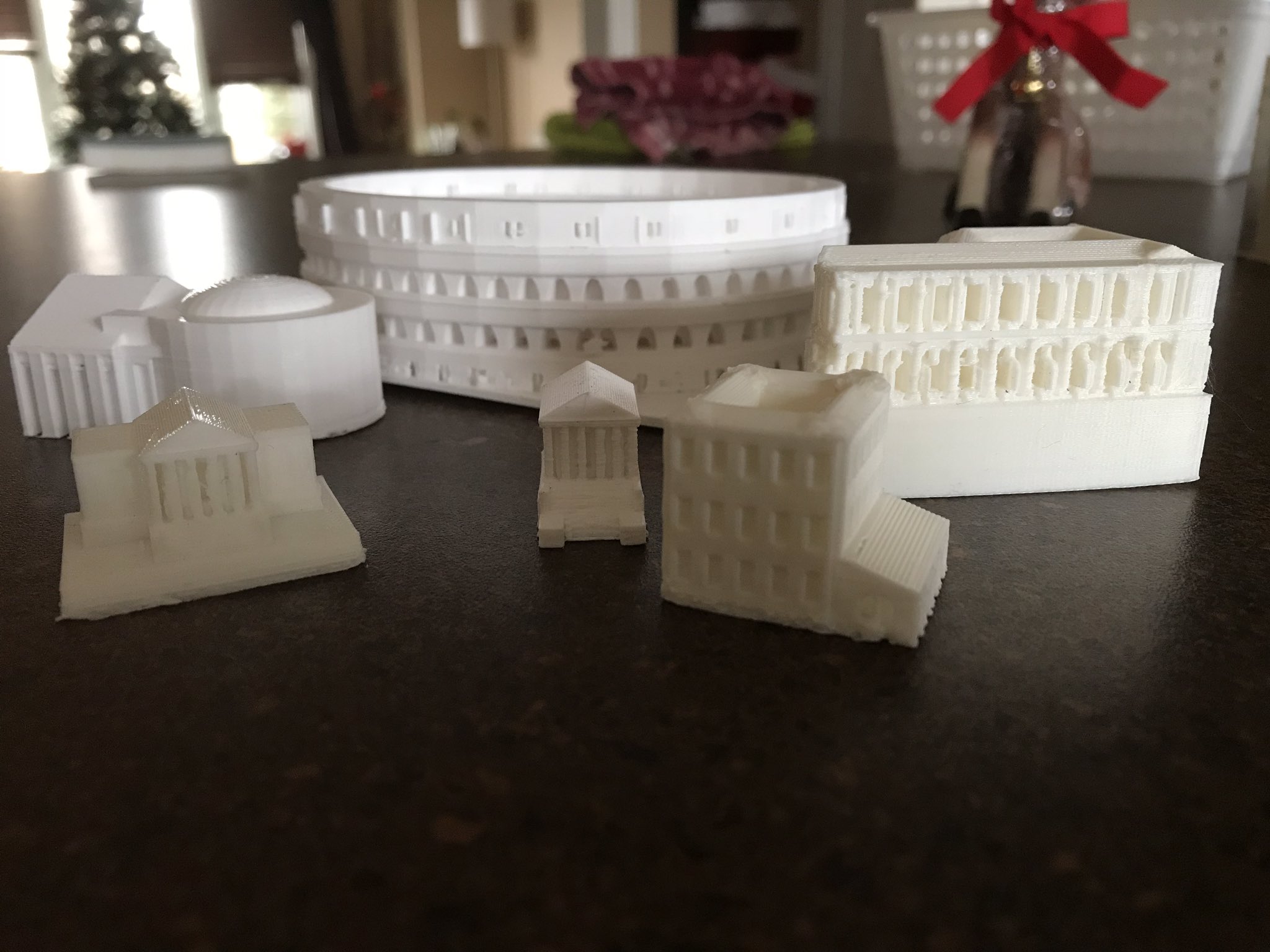

I was so excited about our initial progress that I printed a version of the Flavian Amphitheatre as a test run. We learned a great deal from this first attempt. First, it helped us decide on our scale. By comparing the length of our version of the Amphitheatre to the actual dimensions, we determined that our map of Rome would be roughly 3 by 3 metres. Initially disheartened by the sheer size, we realized that this actually worked to our advantage: recreating sections of the map on 1 x 1 metre squares of paper (and, eventually, cloth) would allow us to not only capture the size of Rome but also create walkways for viewers. We also learned something important about 3D printed models: namely, they need cleaning. I still remember the moment when we realized that the outer layer of our Amphitheatre was a support structure that needed to be removed; suddenly, our builds were much more impressive.

Background 1 The Flavian Amphitheatre with building supports

Background 2 The Amphitheatre with supports removed

Background 3 The Circus Maximus, pre-cleaning. Students use tweezers to remove most of the debris

Students network with a variety of communities/groups and use an array of technology appropriately to work with others.

Admittedly, Rebuilding Rome is not our first foray into 3D. Last year, I started the Scanning History Project, through which my students have scanned museum artifacts and turned them into 3D models that can be accessed online (check out this model of a 8000 year old Mastodon jaw from Ska Nah Doht museum). We also regularly examine 3D sources like the British Museum’s upload of the Rosetta Stone; viewing the artifacts in 3D allows students to examine primary sources in ways that transcend textbooks.

Still, Rebuilding Rome is a different beast, so we needed to talk to some experts. We had a Skype call with Thomas Flynn, the Cultural Heritage Lead at Sketchfab, who is responsible for many of the amazing scans the British Museum has available on Sketchfab. Next, we chatted with Stephen Reid of Immersive Minds, a company that works closely with Microsoft, historians, and archeologists to reproduce historically significant structures in Minecraft. These brief talks helped us understand how 21st century technologies are helping historians depict the past. Our interactions with experts weren’t limited to tech, however. Just before the Christmas break, one of my students was struggling to find useful sources about the Tabularium, a building that seemed to have served several purposes. We emailed Dr. Shawn Graham of Carleton University; Dr. Graham, whose initial area of focus had been Ancient Rome, had chatted with us earlier in the semester, and has always been willing to talk to my students. The student and I co-crafted an email to Dr. Graham; he responded in less than a day. Now, the student needs to add correspondence with a professor to her list of sources.

The last weeks of semester one will dominated by culminating activities and review days. In those last days of the course, we hope to find some time to complete our portable version of the Eternal City. Will my students be worried about exams? Certainly. I’d wager, however, that Rebuilding Rome will stick with them for much longer than anything they write in their study notes.

Jim Pedrech is a HIstory teacher with the London Catholic District School Board and a Microsoft Innovative Educator Fellow.