Ann Posen is a long-time volunteer at the Textile Museum of Canada. She was the 2013 recipient of the Ontario Association of Art Galleries Volunteer Award. Risa e-interviewed Ann this month.

How long have you been volunteering at the Textile Museum of Canada? How did you first end up there?

I retired from teaching in 1996 and decided to look for some volunteer work. I had always been a knitter, and had been to the Textile Museum a couple of times. When I contacted places like the ROM and the AGO, both places had robust volunteer programmes already and would only agree to putting my name on a waiting list, with no guarantees of calling me within a year. Then I called the Textile Museum and went down to interview with their contact person. They were very interested in the fact that I had just retired from teaching and still liked students enough to want to interact with them in a museum setting. The small group of docents at the time had not had any new members for several years, and none of them really liked to tour student groups. At the same time the museum had been given a grant to install a small space for education in the museum. A curator had been hired for education but there was really no programme. What do you do with 20 or 30 students when they show up? It looked like something I was interested in developing, while learning about textiles at the same time.

The museum does a lot with contemporary culture. How does history factor in?

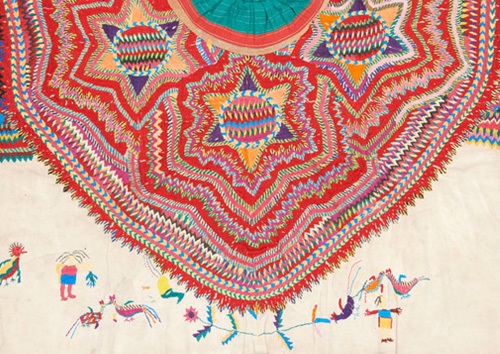

Well, before a cave man could use an axe or a club, he had to learn how to twist plant fibres or animal sinews into a rope to tie the head on to the axe. The spinning of fibres is one of the very first skills that separates man and beast. We have found clay spindle whorls (the little cups in which to spin the spindles) in the earliest of human cave dwellings and remains. Every continent produced methods of producing textiles for warmth, shelter, and clothing. Each new development arose out of necessity. At the same time there was always an element of beauty as well as usefulness. One of the most beautiful carpets existing today is the “Pazyruk carpet”, found frozen in the steppes of northern Russia, dating back 2500 years, woven in beautiful colours of natural dyes, depicting rows of soldiers and animals marching around it. It is of thick wool pile, with hundreds of knots per square inch. An appreciation of beauty seems to have developed along with weaving. Colour, design, and embellishment were never actually necessary, but humans seem to crave them and appreciate them. So in all of our exhibitions, whether contemporary or historical, one of the major considerations we give in all our tours is the techniques used in making each piece. There are many long traditions of weaving, dyeing, braiding, and embroidering that go into making a textile, whether for contemporary art or in a traditional piece of cloth. Modern artists begin by learning the ancient techniques, and from there they begin to express their own modern ideas. Even with new “space age” materials, there is a dependence on traditional methods in using them.

How much research do you do to lead the tours?

For each new exhibition we have time ahead of the opening to research both the history and the artists. The docents meet once a month to discuss the exhibitions and how to tour them, and the curator for each exhibition makes time to come to talk to us, and walk us through the show, giving us background information and answering our questions. There is an excellent library in the museum that we can use, and we all contribute some research and help out the newer docents to understand the show. We do not have a set talk to memorize. Rather, we learn what we can about each piece, and then are free to tour a group according to their interests. This system works well because we can adapt each tour to the interests of the visitors. In terms of hours spent, I guess I would say a minimum of 4 to 5 hour study per show, more if it is a big topic like kimonos or carpets, and less for a smaller show by a single artist.

How do students react to the textiles?

I love taking students through an exhibit. They notice a lot. If you start with what they see or what they know, and begin to explain from there, then a tour is a trip of discovery. One of my favourite anecdotes involves a class of some 25 7-year-olds, in grade 2. And they were visiting when we had a huge exhibition of Persian and Turkish carpets. Where to begin? I asked them if anyone knew anything about carpets. A small hand went up and a voice said: “The old ones used to fly!”. Great! Now we could look at how the carpets were made, and for whom, and with what, and soon we had spent 2 hours “on the silk road” so to speak. Lots of excitement and looking for patterns, colours, shapes, symmetries, and maps of the Silk Road. Another very contemporary show featured a soft pink wall sculpture entitled “Marilyn”. I was touring a group of students from Sheridan College. When I asked who Marilyn was nobody could answer. Someone thought maybe it might have been Marilyn Manson. I felt really old! I had to start at the beginning and talk about Marilyn Monroe, and explain that no, she wasn’t sexy like Madonna, and what her importance was to film and the portrayal of blondes in film, and what she was saying about our modern views of women. In short, we always try to find a way to pull the students in to the work they see. In addition to a 1-hour tour, all students then have a hands-on experience making something relating to what they have just seen. Lots of kids learn through doing. Everyone leaves with something they have made that day that relates to what they have just seen. Both boys and girls love to design and make something for themselves.

We also deal in social history—everyone has a mother or grandmother who knits or sews or helps the children pick out their clothing. Everybody has a favourite blanket or tee shirt or other textile and wants to tell about it. We all wear clothes!

We can gear our tours to math, history, social studies, geography, chemistry—you name it. Cloth tells it all!

What is your favourite artifact, and why?

It is hard to choose just one—so many pieces have fascinating stories. We have pieces of cloth from Sulawese which are printed with designs of spears and weapons or with spindles and needles. A pregnant woman winds each cloth over her unborn child, and it is believed that the baby decides for itself whether to choose the weapons or the spindles. They decide their gender for themselves. This often sparks lots of interesting discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of each! I love “folk art” in particular. Items made for strictly utilitarian purposes, but which are coloured and patterned and made with great charm and beauty. These would include the long, narrow woven bands about an inch or two wide, but several hundred inches long, woven to hold down the skins covering a yurt—a skin-or felt-covered tent out on the Russian steppes. Or the small hooked mats from Newfoundland and eastern Canada, made from shredded fabric no longer usable as clothing, and punching the long strips through old burlap sacking with a hook or bent nail. Think of it. These were made by women in small fishing shacks, in winter, out of nothing. They had no amenities, and in winter on a cold wooden floor, a small mat would provide a bit of comfort. And they are charming—usually pictures of the village or flowers, or fish, or family pets. One shows the family cat, traced as it slept on a piece of burlap, and then used at the design. There is always a need to bring comfort both physically, but aesthetically as well. None of these things was ever made to wind up in a museum. They were made for the family. I love to think of the skills of these hard working women, no matter where they lived, doing weaving or hand work by candle or lamp light, making warm socks, mittens, sweaters, caps, blankets, and rugs for their families. I guess I love this kind of work because it is such a tribute to past times, where hard work and few resources were no blocks to skill and inspiration. At the same time, I love the grace and sumptuousness of some silk carpets from the palaces of the far east. From the cultivation of the silk and wool, to the dyes, to the intricate designs, we can get a glimpse into the court life of ancient Persia. The Japanese have a saying that “every thread has a life”, and I’ve come to discover that in a textile museum, it is certainly true!

Ann Posen