In a recent report from Civix Canada, entitled Civics on the Sidelines: A National Survey of Canadian Educators on Citizenship Education, it was concluded that 63% of teachers believed that an increased focus on STEM in schools has led to a reduction in priority toward Civics education. This highlights a growing concern among educators that the STEM subjects may be overshadowing Civics and History.

What is overlooked is that Civics and History can play a role in advancing and supporting STEM education through the integration of the Design Thinking Model.

STEM, while an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math, is also a pedagogical shift that can be seen in many subject curriculums in Ontario. The goal of STEM education is to promote cross-disciplinary approaches in the classroom. This in turn, will help in the development of “future-ready skills” which encourages students to adapt to (and in) the job market of the future. This is a lot of edu-speak that essentially means teachers should find creative ways to engage students through the use of resources typically found in other disciplines, such as math, science, engineering, and technology.

Stakeholders, like the Ministry of Education, school boards or school administrators, often lose sight of this alternative definition and as a result will dismiss the humanities, lessening their priority when it comes time for course offerings and course selection. For example, STEM courses are often provided with funding and resources due to their perceived importance for future job markets, while Civics and History are frequently relegated to a condensed summer school format, making it challenging to equip students with the skills necessary for active participation in a democratic society.

Years ago, seeing the number of sections of History dwindle in my increasingly STEM-focused school, I started to shift my way of thinking when lesson planning. “If you can’t beat them, join them” became a personal motto. I began to take risks and embrace instructional strategies that deviated from traditional lecture-based, teacher-centered approaches, which gradually transformed my classroom. Doing so allowed me to better integrate the principles of STEM education and as a result it boosted both student engagement and interest from parents and administrators. As an added bonus to this pedagogical shift, it became increasingly difficult for students to utilize generative AI like ChatGPT to write their work for them. And if they dared to regardless, it was blatantly obvious as the AI bot could not appropriately reflect upon the specific engineering and designing done by students in class.

There have been strides to transform how topics within the humanities are taught. There are educational initiatives like Heritage Fairs where students investigate a topic that they’re interested in through a variety of media in order to showcase personal family history or local stories and geography. They are then assessed by local historians who ask questions and provide feedback on their work. This is, at its core, what the STEM principles of Design Thinking are. Design Thinking is, according to edutopia, “an approach to addressing challenges in a thoughtful and fun way, where you apply collaboration, creativity, critical thinking and communication.” When you organize assessments using the Design Thinking structure, students become engaged in the learning process and they will generate innovative solutions and the end result is a deeper understanding of the subject material and real-world skills.

But approaches like a Heritage Fair can feel daunting, especially within a semestered timeline where there is often an expectation to test content knowledge or work toward a final exam. Many boards mandate high stakes testing like a final exam, so how can a teacher effectively incorporate the foundations of STEM and Design Thinking under time and content constraints?

Finding small ways to weave STEM or Design Thinking into your curriculum is the easiest way. Students will still be evaluated on curricular expectations, but instead with Design Thinking, you structure your evaluations in a way that allows the students to not only be the engineers of their learning but become engaged in the subject’s content in a unique way.

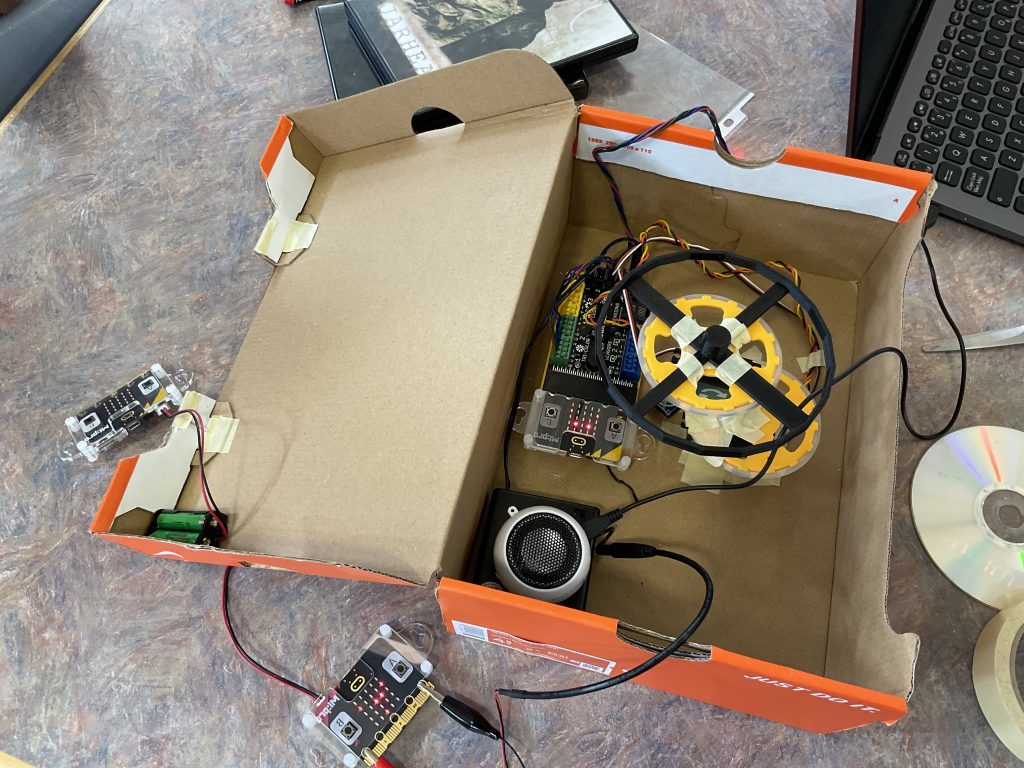

For example, in my grade 10 History class, students research a decade in Canadian history and become experts on topics relative to a particular theme (eg. Equality, Canada-US Relations, Science & Technology). From there they work with a group to develop a comprehensive product that is reflective of the achievements and key moments from their decade, while employing the historical thinking skills. Some students will design and code a working robot, create artwork or even 360° virtual environments. They are still researching Canadian history and still actively using the historical thinking skills, but their product allows them an opportunity to demonstrate their understanding in innovative ways. It is not necessary for you, as the teacher, to have coding or technology experience as there are numerous beginner-friendly platforms like code.org and Digital Moment that empower students to explore independently. Often, students come already equipped with foundational coding and digital design knowledge. Instead, your role should be to guide and facilitate their problem-solving and creativity.

Last year I piloted those same principles into my school’s Civics classes. Students were asked to develop a board game that demonstrated the importance of citizen contributions toward the common good. First they have to define who their audience is, determining what they would want from the board game. From there jobs among the group of students were divided with students taking on different responsibilities and being held accountable to completing them in order for the game to succeed. For example, we had a rulebook writer, a component designer and a group coordinator. This allows for students of various academic levels to achieve at what they are best suited for.

In the process of developing their product they were employing science, technology, engineering and math principles. In Civics, students measured the boards to determine the best way to allocate space. Others employed technological enhancements like the use of digital dice or score trackers. The component creators engineered game pieces and rebuilt them if they weren’t effective or if the goals of the game had changed through the design process. Ideally you will want the product testers to provide feedback to the developers. This can be achieved through a Google Form or even a 1:1 session.

In keeping with the principles of Growing Success, any work developed collaboratively should not be subject to evaluation. Instead, I ask students to reflect on their learning and the application of historical thinking or active citizenship in their product. For a 3D model, the students can connect the details of the model to the historical context of their research focus.

Incorporating STEM and the Design Thinking process into your classroom isn’t a pedagogical shift that happens over the course of one semester. It’s something that happens gradually, with small changes here and there until eventually your entire course becomes centered by student-focused activities and assignments.

Below are some best practices to help you begin the shift within your classroom toward incorporating STEM and the Design Thinking model more fluidly.

- Transform your classroom from a teacher-led structure to one that is driven by student collaboration by organizing your student desks from teacher-centered into group-centered.

So many high school classrooms are organized into some variation of a row. It’s an antiquated approach to learning that encourages students’ attention to be on the teacher with the ultimate goal being teacher-centered instruction. It’s how many of us were taught growing up, but it is not always the most effective way for students to learn today.

Instead, shift the layout of your classroom into one where students can better engage with each other. According to Marta Garcia from the Center for Curriculum and Professional Development, by “valu[ing] an environment that encourages students to share [and] make responsible choices, and work productively, we need to consider how the physical layout of the room fosters collaboration and participation.” By changing your classroom layout away from traditional rows or amphitheater style, it will innately encourage you to plan for more student driven activities and change the way that you think about your students’ engagement in the learning process. In clusters, groups or with flexible seating, students are likely to brainstorm, debate and analyze, which builds and reinforces their critical thinking skills. Students will feel more engaged in the lesson when they can actively contribute to their learning in a smaller setting. They will deepen their understanding of skills by explaining concepts to their peers and reflecting on the various perspectives learned.

Remember that the groups should be teacher developed with a variety of abilities represented in each group. This not only helps create a more inclusive classroom, but it encourages students to collaborate, learn through their peers and engage with diverse perspectives.

- Increase the amount of student-centered/small group learning opportunities so that students become comfortable with group work

The ability for students to work together effectively doesn’t magically happen. The process must start from day 1. By actively employing student-centered learning opportunities, whether it’s brainstorming as a group the answers to a key question, working through an Elections Canada activity or evaluating the pros and cons of an issue, forcing students to engage with their peers allows you see which students work well together and which don’t. This enables you as the teacher to make changes in advance of any Design Thinking Project where effective teamwork is integral to the product’s success.

An added bonus to increased student autonomy and group work is that it encourages students to be accountable for their own learning. They will have to rely on each other to work through problems and concepts. For example, for students who’ve never worked in 3D modeling, it can be very challenging to master the nuances of the program. By encouraging my students to reach out to in-class experts or the wider online community (eg. help forums, tutorials, social media pages of the company that manufactured the app or device) it mirrors real-world interactions and lessens the burden on a teacher who may be less familiar with the tool.

As with any skill, working effectively as a team takes practice. The more you encourage students to engage with one another, the more practiced they become and the better the results.

- Be okay with failure

You will make mistakes, the students will make mistakes and everyone will learn from them. Too often we as teachers are ashamed to fail at an idea- sometimes programs don’t work and sometimes ideas just aren’t great. But you need to learn from what went right and what went wrong and try again. We expect this from our students, so why don’t we employ this practice more regularly for ourselves? Recently I’d asked students to include a design developed in AdobeAero, an augmented reality program, into their assignment. As students started working with it, it became quickly apparent that their ability to export their creation was blocked by my district. Rather than get mad at myself or at the district, I pivoted and asked the students to screen record their work instead.

Along these same lines, sometimes the students’ creations don’t quite work. The prototype just might not function how it was expected to. Instead of penalizing students, lift them up. Encourage them to think of how to fix the error, and be reflective about their decisions. This is a key component of the Design Thinking Model as these skills will serve them well as they navigate the working world where not every project will be successful. What is important is how they move forward and improve upon their prototype, or even reflect upon what went wrong.

- Allow students to be the navigators of their final project.

Avoid inserting yourself into the students’ decision making process. While it can be tempting to give them ideas or correct their mistakes, they will learn best through trial and error. Instead, encourage them to keep trying or suggest materials they can use to further enhance what they’re working on.

- Add in reflective practices

It’s important that we remember that a lot of the STEM and Design Thinking practices mentioned above are not explicitly in any of our curriculums. For example in CHC2D, we are asked to explain how various individuals, organizations and specific social changes between 1914 and 1929 contributed to the development of identities, citizenship and heritage in Canada (B3). Rather than evaluating what a student has constructed (eg. a 3D model), consider evaluating their explanation as to how their product is demonstrative of the curriculum expectation. Their explanation can take many forms: a written response, a video or a presentation which allows you to evaluate the connections they’ve made between their product and the curricular expectation.

- Invite administrators and district stakeholders to your classroom

It’s important for administrators to see STEM happening in courses that aren’t specially oriented to Science, Technology, Engineering and Math and the only way for this to happen is to invite administrators into your classroom. In doing so, they will be able to see the creativity that you bring to your content area and it will allow them to witness first hand how students are responding to your lessons. Many administrators are used to seeing History, Civics and the Social Sciences taught through lecture and direct instruction with textbook reading and note-taking as the central way of consolidating understanding. By showing administrators that your classroom engages in a student-centered structure where they are engaged in inquiry, exploration, and collaboration they will see first hand the student engagement which will validate the impact your innovative practices are having. If you are in need of resources (eg. training in 3D modeling, funds for micro:bits), allowing administrators into your room will help them better understand the limitations you might be facing and give you a way to advocate for the necessary support. As an added bonus, it will also allow them to see value in what you do in your courses and they will work to preserve the section numbers in your department whenever possible.

- Seek funding for needed resources

Finding funding support can be tricky in an era of economic austerity that is facing many educators across the province. It may be easier to start small and build resources over time. Financial support can come from many places- parent council donations, grants, or community partnerships. Sometimes just asking your administrator for a special purchase is all it takes and even your school’s SHSM program also may have additional funds to support a purchase. Also keep an eye out for organizations who may offer free products for attending their (also free) learning session. My school’s first set of micro:bits were free through a federal grant that Let’s Talk Science had, which had them come into schools (for free) and present to teachers how to use the micro:bit and as a parting gift, each participating teacher received a set of 10. Since three members of my department had attended, we secured a class set!

Some resources that I have found to be invaluable in my classroom are the following:

Portable White Boards: When I first started teaching, chart paper was used for small group brainstorming. In Peter Liljedahl’s 14 Building Thinking Classrooms, he advocates for non-permanent surfaces to encourage greater risk taking and turning “passive learning spaces into active thinking spaces.” Students feel comfortable using the white boards to brainstorm, adjust, and discuss their ideas and the ability to correct, add to and remove at will, makes a white board an appealing tool. Additionally, unlike chart paper, there is limited additional cost beyond the first purchase and the replacement of dry erase markers.

Micro:bits: These small controllers allow students to use block coding, Python or JavaScript and program various hardware (eg. Hummingbird kits). Micro:bit also offers free training for teachers new to the software.

Bird Brain Hummingbird kits: These kits work in tandem with a micro:bit and provide everything a student could need to develop and operate a robot. From wheels, rotors, lights and sensors, the only limitation is a student’s imagination. Students in my history class have created a ballot box that reveals a referendum vote, a moving television screen, a TTC streetcar and the Canadarm.

3D printer: 3D printers are a great way to get students to develop artifacts through free 3D modelling programs like Tinkercad.

Of course there are various low cost crafting tools that also come in handy like cardboard cutters, scissors, glue and glue guns, paint and paint brushes and craft paper.

- Be fearless

It’s ingrained in teachers that we must always have the answer, despite faculty programs reinforcing the notion that it’s okay to not have the answer. For most of us, however, as history and civics educators, our undergrad and postgrad education did not teach us how to code, use GIS mapping or incorporate 3D models into our course work or lesson plans. And it’s incredibly daunting, especially for those of us who’ve been teaching for over a decade, to even imagine what introducing those concepts could look like in our classroom. How much support might your students require? Can you even support them when they hit a wall? This is where being fearless comes into practice. Take the risk, do the thing that’s hard, and watch your students become empowered. When you don’t know, direct them to places that might know- YouTube help videos, social media platforms, their peers, older students… And when that fails, your students will tinker and try and try again. It builds resilience and when they finally achieve, the excitement in the air is palatable. As Winston Churchill once said “give us the tools, and we will finish the job”- give your students the tools: scissors, micro:bits, Hummingbird Kits, cardboard, glue, paint & paint brushes… and they will never cease to amaze you with what they can create.

Christina Iorio is a teacher with the York Catholic District School Board and is a regular contributor to social media platforms regarding all things history and social science.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/therealmsiorio/