Book Reviews by students of John Myers at OISE.

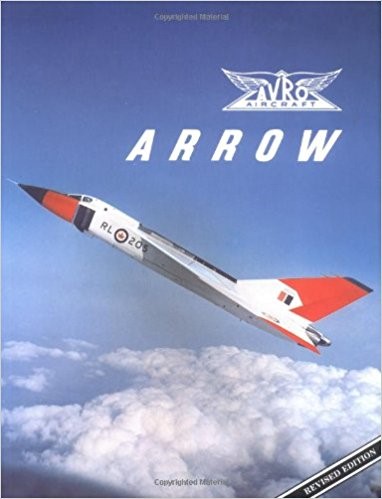

Avro Arrow: The Story of the Avro Arrow From its Evolution to its Extinction

Review by Billy Rowe

The Arrowheads, Avro Arrow: The Story of the Avro Arrow From its Evolution to its Extinction (2004, Boston Mills Press Book), describes the evolution and eventual dismantlement of, arguably, Canada’s greatest military advancement, the Avro Arrow. The book begins with the developmental phase of the project in which the readers can gain an understanding of how the plane was built. The book then goes into the breakdown of the weaponry attached to the plane, such as the development of a new missile, Sparrow 2, and the larger scanner dishes to help detect other planes. Finally, the last part of the book discusses “Black Friday”, where on February 20, 1959, Avro was ordered to terminate production and scrap the current plane.

Ultimately, the book provides the readers with not only a historical story, but also a mechanical break down of the aircraft, and uncensored government documents. Although Canada is often not seen as a producer of advanced military weapons, the period after World War II displayed a potential growth in their abilities that produced an aircraft that far surpassed the United States, but unfortunately was never utilized. The book’s insight into Canada’s military history can be utilized in the Grade 10 Canadian History course as it provides context into how the post-war period shaped Canada and what attempts we made to strengthen our power.

I would shape my post war unit to focus on events in Canadian history that portrayed us as being a more independent country and developing our relationships with other countries and groups of people. Such topics I would include in this post-war unit are: the Sixties Scoop, the 1967 World Exposition, the October Crisis, and Diefenbaker’s dismantlement of the Avro Arrow. Often, these topics are skimmed over because of time constraints in the semester.

However, I would create an end-of-semester inquiry-based assignment in which all the students receive a different topic for an event that occurred after World War II. During the inquiry assignment, each student would be required to utilize a specific book about the topic, such as Avro Arrow: The Story of the Avro Arrow From its Evolution to Extinction, in order to help in their research. Then the students would input their information into Google Slides and we can use this to discuss some of the major events that took place after World War II in Canada, with the limited time that most classes face when going through the Grade 10 curriculum.

Obasan

Review by Mary Kate Grey

The overall course theme will be Social Justice. The foundations of the course will look at people and events through the lens of resistance (violent and non-violent), surveillance and anti-racism, and anti-oppression with the idea that students will have a variety of opportunities to learn about diversity and diverse perspectives. In accordance with the curriculum, the course will draw attention to the contributions of women, the perspectives of various ethnocultural, religious and racial communities, and beliefs and practices. The broader purpose will be to guide students to a place where they understand that the events studied in the classroom impacted different people and communities in different ways.

In the grade 10 curriculum C2. Communities, Conflict, and Cooperation: students are expected to describe some significant interactions between different communities in Canada, and between Canada and the international community, from 1929 to 1945, and explain what changes, if any, resulted from them. One of the communities I would like to examine is the Japanese community interned during World War Two and focus specifically on forms of resistance and forms of surveillance. Often, the ways in which this subject has been taught leaves the impression that Japanese Canadians passively stood by and let this happen. It is crucial (I think) that as we examine these forms of resistance we also examine the ways in which we remember the people and events. Therefore, I think a shift in how the internment of Japanese Canadians gets taught needs to happen so that the “other” perspectives are heard as well.

Rather than have the students read the entire book Obasan by Joy Kogawa, I would have the students examine points of resistance through the letters written by one of the main characters, ‘Aunt Emily’ in the early war years, and compare them to the letters written by her nearing the end of the war. Students would also identify areas where Japanese people were surveilled, such as the young children in schools, by reading excerpts from the book. Students would then have the opportunity to examine the collection of documents in Library and Archives Canada to see how many people were re-patriated and moved to camps. Students would have the opportunity to study the maps, pictures and letters of people like Thomas K. Shoyama and photographs such as the following (from library archives):

One photograph, 1910, depicting Messrs. Kohashigawa and Takayesu, immigrants from Okinawa, Japan, in Lethbridge, Alberta (accession 1976-004 NPC): Acquired from K Kohashigawa,

33 photographs, 1942-1950, depicting activities of several Japanese-Canadian families evacuated to Kaslo, New Denver, Slocan, and Vernon, British Columbia, also Coaldale and Tabler, Alberta (accession 1976-089 NPC): Acquired from Margaret Ridgeway, Vancouver, B.C.

Copies of 14 photographs, 1942-1945, depicting activities and staff of the Slocan Community Hospital, New Denver, B.C. (accession 1975-418 NPC): The original photographs were loaned by the Ethnic Archives (from the M. Uchida papers) and copied. The originals were returned to the lender.

One photograph, 1946, depicting the embarkation of Japanese-Canadian internees, Slocan City, British Columbia (accession 1975-421 NPC); One photograph, ca. 1943, depicting the Tashe, British Columbia, overflow camp, a non-denominational internment camp for Japanese Canadians (accession 1975-377 NPC): See textual records, above.

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/le-public/005-1142.27-e.html

Throughout the examination of the primary documents, I would have students classify and label the documents in various chart forms that they believe to best organize their work. The students will then analyse the documents and work to identify limits and possibilities within the process of resistance during WW2. Further to that, the students will be asked to consider if those limitations still exist today for some groups of people.

Ideally, throughout the year there would be an examination of other events so that the students can see where issues of race, class and gender (but not limited to) intersect with the different interactions between communities throughout Canada.

Guns, Germs, and Steel

Review by Christina Kompson

The World History course for grade 11 is organized in strands of inquiry and skill development; rise, success, decline, and legacy of civilizations. While most teachers guide students through a predetermined set of civilizations, Jared Diamond’s

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies offers teachers another option for structuring the course. The book is a staggering 440 pages long and takes the reader through a detailed and captivating narration of human history. The first paragraph in the Preface gives a straightforward explanation to why this history might be important for students in an Ancient Civilizations course:

“This book attempts to provide a short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years. The question motivating the book is: Why did history unfold differently on different continents? In case this question immediately makes you shudder at the thought that you are about to read a racist treatise, you aren’t: as you will see, the answers to the questions don’t involve human racial difference at all. The book’s emphasis is on the search for ultimate explanations, and on pushing back the chain of historical causation as far as possible” (9).

What a fantastic start to a course on human history! The first two parts of the book, “From Eden to Cajamarca” and “The Rise and Spread of Food Production” (up to pg. 190), could be read in class and for homework. The book is written accessibly, but it is certainly academic, and gives teachers a number of opportunities for students to develop their historical reading and writing skills. The anti-racist analysis allows for a number of entry points for social justice conversations that can link the course content to students’ lives. Diamond’s work centres around food and the ways in which humans adapted to (and adapted for their use) sources of nutrients. This thread throughout the book reframes history around community survival and success rather than influential leaders and major events, a refreshing take on teaching history. Furthermore, because the book describes the interconnectedness of the ancient civilizations, it sets up a number of big questions that can guide investigation of the individual civilizations. It is a truly interdisciplinary history, and the potential to tap interdisciplinary learning is exciting!